Evolution not Revolution

Small Steps to Deliver a Grand Vision

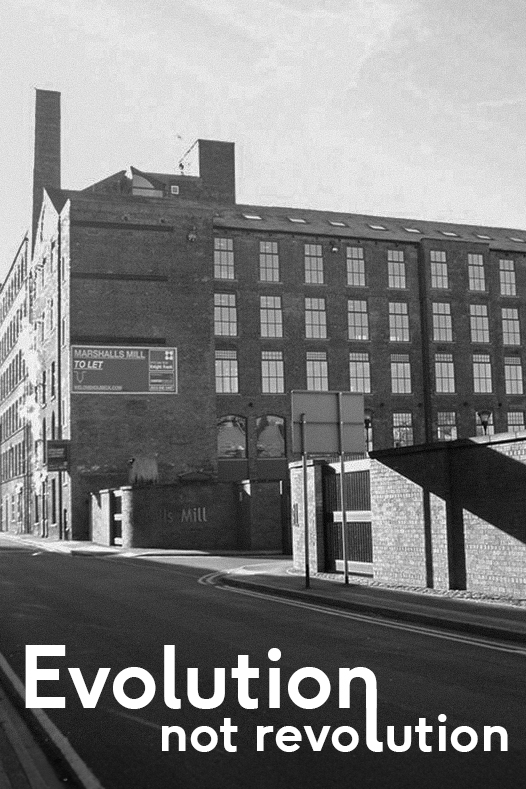

Marshall’s Mill is a significant and imposing seven storey red brick Victorian mill set in Leeds' creative quarter. The refurbishment works to the Mill adopted the five ways to well being to explore a different design approach.

Context

Leeds is the fourth largest city in England with reputedly the second largest financial and legal sector outside of London. It is a successful city. Leeds, like many core cities, benefitted from the previous government’s strategy of promoting quality, cohesive and holistic design through the work of the Regional Development Agency, Yorkshire Forward, and almost uniquely a civic architect, John Thorpe, and an urban design team within the council. The skyline of Leeds has developed over the last decade, but few of the large grand visions and master plans for the centre have materialised.

A successful regeneration area is Holbeck Urban Village. The area is south of Leeds railway station, the river and the canal. It was at the heart of the industrial city boasting factories foundries and mills. Several buildings have survived from this period and the Round Foundry development is recognised as an exemplar of regeneration, mixing new buildings with refurbishment, creating offices, homes, restaurants and cafes. It isn’t surprising, therefore, that the area and buildings are popular with creative businesses and the original aspiration to create a creative quarter has all but materialised.

Marshall’s Mill is a significant and imposing seven storey red brick Victorian mill with a cast iron structure and towering chimney. Built by John Marshall in 1791-2, it was less glamorous than its neighbour, Temple Works (a homage to the brilliance of the Egyptians) and it was a symbol of Marshall’s confidence that he was a pioneer of the industrial revolution creating a new world, an empire in a similar way to the Egyptians. Both buildings were at the forefront of technology. Temple works created (at that time) the world’s largest covered space, naturally lit from above with an ambient temperature sustained by an insulated green roof, rain water collection and under-floor heating. The adjacent Mill was built to weave the flax created in the works. Marshall’s Mill doesn’t exhibit the same exuberant narrative as the works but it too was a technical achievement in its day. The brick and glass walls achieve a solid-to-opening ratio of 45%, with the outer skin supported on a cast iron structure. This provides the Mill with a fantastic interior quality. The narrow floors are flooded with light from all sides and the stone flag floors are supported by brick vaults. Marshall's achievement is not immediately apparent as we expect post industrial buildings of this character to be of a certain quality but we must realize that this building was one of the first of a kind built decades before those that we are familiar with today. Both Marshall’s Mill and Temple Workshare recognized by English Heritage for their historical importance.

The grade two listed Mill and its grounds sit on the opposite side of Marshall Street to the Round Foundry and were not part of the extensive regeneration investment made just after the Millennium. The Mill was refurbished for commercial office use in the early nineties. The refurbishment works effectively sought to cover up the idiosyncrasies of the Mill, to sanitise its interior, and create an office space that, as much as possible, could emulate its Grade A new build counterparts in the centre of town. With the benefit of ample parking and easy access to the centre, and transport, the Mill has been successful as an office destination, providing reasonably large spaces at cost effective rents. This relative success meant that little needed to be done but this is a strategy that is reliant on there being a buoyant market and a demand for office space.

1. Marshall's Mill

The market is no longer the same. With the economic crisis, a change of government, the bonfire of the ‘quangos’ and businesses reviewing their operations and efficiencies the demand for commercial office space in Leeds and across the country has changed. The Mill has been reasonably well used since its refurbishment and up to 2009 was 80% let. There has been a steady decline, with businesses moving out, either through retraction, relocation or closure, no new lettings and very few enquiries. In May 2010 the Mill could only boast 11% occupancy. The Mill has never charged top-end rents for its space but neither was it the cheapest space available. An option would have been to reduce rents in an effort to secure existing tenants and attract new ones. The problem with this approach is that it undermines value.

The Mill was bought in 2003 through a pension fund and managed by a development company. The company’s interest is in protecting value, and ideally enhancing assets, and creating wealth. The new owners not only acquired the Mill but also the adjacent Round Foundry. Their perspective was long-term rather than short-term. Their purchase demonstrated an investment of confidence in the creative quarter. What could they, therefore, do to prevent loss of value, protect rents and secure new tenants?

The decision was made to invest. If the Mill was to capitalise on the success of the creative media-focused area of the adjacent Round Foundry, still attractive to the market and securing good rents, then the nature, type and size of space provided at the Mill needed to complement its neighbour by offering something different and distinct. The address, place and space needed to reflect these creative industries - businesses which are known to be focused on the individual needs of their staff who work in a relaxed atmosphere rather than in more formal spaces as their corporate counterparts do.

Strategy

Having identified that these new and growing businesses were following the trend to be more focused on the well being of their staff, the design team reviewed the development of the Mill from a user perspective and considered what makes people feel good about their place of work.

The coalition government had already identified the importance of mental health and well being in the population in their White Paper, Healthy Lives Healthy People[i] and from this the Office for National Statistics (ONS) was asked to develop a set of indicators that measured national well being. The ONS’s research indicated that those individuals with a better sense of well being and happiness were inclined to be more involved in social and civic activities, behaved in an environmentally conscious way, and had stronger relationships and were more productive at work.

The strength of this research created a positive strategy for the government based on what to do rather than what not to do and importantly that this was within the individual’s control. Further to this academic research the new Economic Foundation was commissioned to develop a mental health equivalent of the popular and well known message that people should eat five portions of fruit and vegetables a day in order to maintain good physical health. The result was five ways to well being.

The architects for the refurbishment works to the Mill adopted the five principles to explore a different design approach. They addressed the design in such a way that it responded to the individual and shifted the perception away from the anonymity associated with the Mill as depicted in Lowry’s work where the individual is reduced to the single black silhouette over-shadowed by industry

Five ways to well being

Connect…

‘With the people around you.

With family, friends, colleagues and neighbours.

At home, work, school or in your local community.

Think of these as the cornerstones of your life and invest time in developing them.

Building these connections will support and enrich you every day.’

The Mill has been hemmed in - its inhabitants municipalised by the security barrier created by the external walls and blandness of design. Huge iron utilitarian gates defend the grounds from intruders but are left open rendering their protection useless and un-administered despite the prevalence of cameras which now monitor the approach.

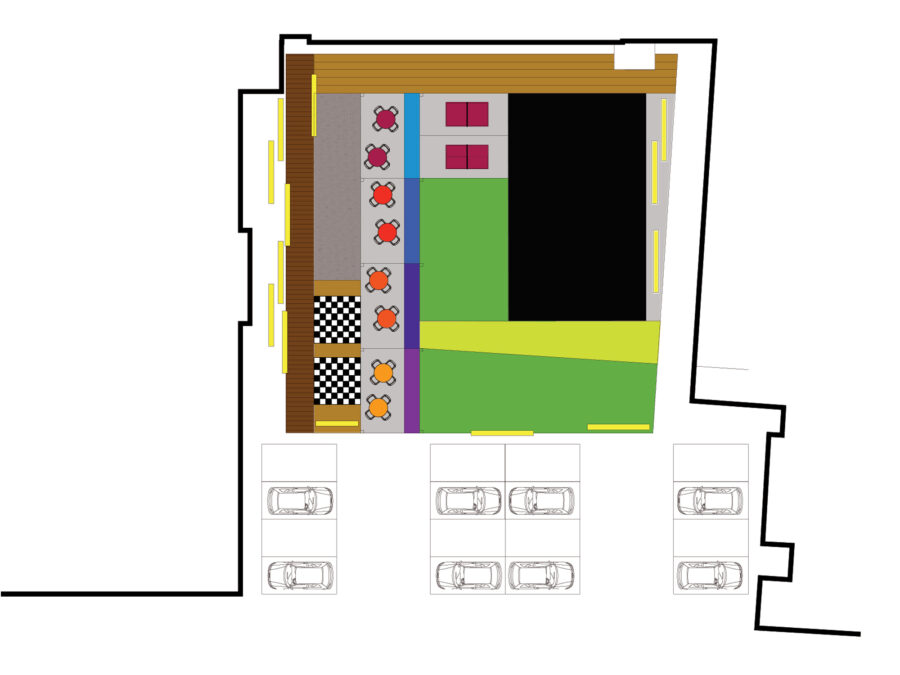

This is not a welcoming, warm or inviting place. The message is to keep away. The design team wanted to reverse this perception. They wanted to transform the perception of the Mill, to create an address, to make it inviting, accessible and hospitable. To create an environment at the curtilage of the Mill that was attractive and one in which people might linger rather than run. Their inclination was to open the Mill up. The Mill’s entrance is concealed from the street so the concept was to transform the street frontage, take down the walls and replace them with a forest of trees. The forest would be temporary; an intervention which would occupy the plots of the building’s past and of those planned for in the future (when there is sufficient confidence in the market to invest in the wider development master plan). This forest would become mythical, a ghost of buildings past and a promise for the future, a landscape into which anything is possible. The concept has evolved to create a new and welcoming forecourt to the Mill, one which links it physically and aesthetically with the investment and the custodial care already associated with the adjacent Round Foundry.

Be active…

‘Go for a walk or run. Step outside. Cycle. Play a game. Garden. Dance.

Exercising makes you feel good.

Most importantly, discover a physical activity you enjoy and that suits your level of mobility and fitness’

The inner courtyard is filled with cars. It provides nothing more than a slightly shorter walk from the car to the door. Having created a front garden to connect with the surrounding area and re-defined the streetscape, in order to create equilibrium the architects identified the opportunity to transform the courtyard into an activity playground and a garden for the occupants of the Mill as well as a visual amenity. External gantry fire escapes were elevated beyond the functional to become ‘decked’ break-out areas (balconies) for each of the overlooking floors. This in turn reinforced the connectivity of the external areas to the internal space in the Mill. As individuals break away from their desk activity they are able to use their personal mobiles whilst standing on the balcony which overlooks a giant ’Suduko’ puzzle set by the centre manager, or to watch ‘creatives’ playing basketball. The ethos of the design approach is to move beyond function towards a celebration of possibility, to engage with the building users as you would residents who have a sense of ownership and pride. In addition to the courtyard garden, made up of raised lawns, seating areas and a ping-pong game, the Mill complex includes a refurbished out building which provides gym facilities and exercise classes.

Take notice…

‘Be curious. Catch sight of the beautiful. Remark on the unusual.

Notice the changing seasons. Savour the moment, whether you

are walking to work, eating lunch or talking to friends. Be aware

of the world around you and what you are feeling. Reflecting

on your experiences will help you appreciate what matters to you.’

The refurbishment is principally about the creation of new office suites of varying sizes throughout the Mill but it is the in-between spaces, the non-revenue generating spaces that are able to add social value and create distinction. It is the in-between bits that are able to change, reflecting the diversity of the new inhabitants, and the new businesses. Throughout the refurbishment, the architects have been careful not to eradicate past decisions and interventions to the Mill. They have exposed and uncovered parts of the history of the Mill and celebrated these. The previous renovations have been removed, repaired and revised but care has been taken not to impose a singular style and monopolise the spaces. The idiosyncrasy of the Mill has been celebrated by, the diversity of its inhabitants and the complexity of its history which makes the Mill what it is today. Throughout the design, the architects have looked for opportunities to express these narratives either by, for example, exposing cast iron doors or allowing the occupants to overtly express their company graphics and the characteristics of their staff and business. They are allowing the environment to change. The success of this approach is reliant on a change in management philosophy. The management company needs to be creative and to become proactively involved rather than policing and sterile.

4. Revealing History

Keep learning…

‘Try something new. Rediscover an old interest. Sign up for that course.

Take on a different responsibility at work. Fix a bike. Learn to play an

instrument or how to cook your favourite food. Set a challenge you will

enjoy achieving. Learning new things will make you more confident as

well as being fun.’

By concentrating on the in-between spaces and the opportunities for the occupants of the Mill to come together and share, the architects hope to develop a sense of community where individuals meet and engage in dialogue; possibly developing new business-to-business relationships and also to learn about other businesses and how their experiences or services may benefit each other. The reception and lobby areas are not the expected cold corporate environments filled with ‘Miesien’ furniture that never get sat on. They are more akin to a café, with tables and chairs frequently in use, with magazines and book exchanges littering surfaces; they are places to be occupied by people waiting for friends and exchanging information with other occupiers, and with the management. To further this sense of blurring the definition of the office as a closed environment, the architects look to introduce shared facilities, meeting rooms, that can be used by the businesses but that can also accommodate space for ‘learning lunches’ or evening classes. When full, the Mill will accommodate c. 800 people. This number could be recognised as a village community. The building will be able to provide facilities to engage, entertain and educate this wider civil society as well as providing a distinct office space.

Through the development of the Mill and the adoption of the ‘five ways to well being’ the architects have tried to create an evolving situation. They are no longer trying to determine a grand master plan which is a prescription for the future which can only be delivered when the right economic conditions exist, and is in direct response to a single perspective. The architects are developing an evolution for the building and incrementally moving towards the delivery of a long-term vision. This approach allows for flexibility, re-interpretation, change and the development of original ideas, and provides an impetus for change. Flexibility enables new ideas to be explored.

The regeneration of the wider area hasn’t been as rapid as previously hoped and demolished buildings, vacant plots now vie for use as surface car parks. The architects are in discussion with the City Council about the possibility of using these spare plots to create a new landscape of urban forests which could potentially fuel a biomass boiler for the Mill and other adjacent buildings -a community energy centre. These ideas might prove unattainable but because the master plan is no longer a set of rigid ideas, however wild, alternative opportunities can be pursued.

Conclusion

The role of the architect and designer has the potential to progress. This emerging role relies on establishing the right sort of relationship with the client, where both architect / designer are able to secure their involvement with the evolution of ideas and the search for possibilities, as opposed to the description and translation of an already formulated solution - a further iteration of a well established tradition in designing and planning space.

Hans Venhuizen , in his book ‘Game Urbanism: a manual for cultural spatial planning’[i] presents the idea of a new role, the plan master or concept manager. This is a role which moves away from the draughts person defining a solution for creative innovators and directors orchestrating a dialogue of the possible with the client, investor and stakeholders and then helping to make this a reality. With this conceptual approach there is a greater emphasis on the process and a willingness to be actively involved as a participant.

In adopting the ‘five ways to well being’ for the development of the Mill the architects have been able to use each of the five themes to independently analyse all of the design ideas presented by all those involved in the project. Everyone’s ideas are valid and need to be tested and explored.

Everyone involved with the Mill buildings and its surroundings are travelling together on a journey in pursuit of change and development, they have an intention but are not beholden to a fixed outcome. The architects now have the opportunity to become creative directors involved with the imaginative management of an asset and in this way to maintain creativity and conceptual continuity so that other small investments can multiply and eventually deliver whole-scale conceptual change which with hindsight could be described as visionary.

Bibliography

- [i] Aked, J. and Thompson, S (2008),Five Ways to Well Being(NHS Confederation, nef)

- [ii] Cox, E., Squires, P., Ryan-Collins, J. and Potts, R (2010),Re-imaging the High Street, The 2010 Clone Town Report, (nef)

- [iii] Venhuizen, H. (2010), Game Urbanism - Manual for Cultural Spatial Planning pp.29–37 (Valiz, Amsterdam)