Liberation

Being open to Exploration in China

This essay results from an excursion to Wuhan China in 2013 to present two projects to local and central authorities, and the introduction of a third project whilst in the country.

All three development proposals are enormous in scope and ambition. They are related to leisure and culture and are quite extraordinary in comparison to common projects experienced back in England. This differentiation sometimes led us to question the reality of these ambitions – they were quite literally unbelievable and however outrageous the design proposals the client’s appetite was never quite satisfied.

Our experience in China; being treated like dignitaries and hosted with extravagance, was exceptional and in stark contrast to the way we work with some clients at home. The contrasting treatment and ambition to those experienced in the everyday was disorientating, certainly not un-pleasant but dislocating. We began to feel a need to contextualise the phenomena in a way that would enable us to better understand and appreciate the experience.

The media in England over the last decade has illustrated the stark contrast in architectural expression between the depressed economies of the west with the rise in popularity of restrained integrity and eschewing of decadence with the burgeoning economic growth of the Arab Emirates and China with their salacious exuberance and proliferation of mega-structures. There is almost an institutional cynicism and a feeling that this is so far removed from our reality that it lacks meaning and therefore relevance.

In an attempt to contextualise the projects and their exuberance we compared them to the grand gestures associated with the world fairs of Paris 1889 and London 1851 with their iconic structures; the Eiffel tower by Gustave Eiffel and Crystal Palace by Joseph Paxton. In both circumstances the architecture resulted from huge economic growth, growing urban population and the potential exploration of international markets.

On returning home I decided to explore this parallel to determine whether this comparison was just and whether the outcomes of the industrial revolution bore any relation to the new architecture emerging in China and to the projects that the office was involved with. It is with some trepidation that I have attempted this as I am aware of the complexity surrounding development in China and also of the Industrial Revolution in 18thCentury Europe.

Mass Urbanization

“What happened to the land determined the life and death of most human beings in the years from 1789 to 1848. Consequently the impact of the dual revolution on landed property, land tenure and agriculture was the most catastrophic phenomenon of our period. For neither the political nor the economic revolution could neglect land, which the first school of economists, the Physiocrats, considered the sole source of wealth, and whose revolutionary transformation all agreed to be the necessary precondition and consequence of bourgeois society, if not of all rapid economic development. The great frozen ice-cap of the world's traditional agrarian systems and rural social relations lay above the fertile soil of economic growth. It had at all costs to be melted, so that that soil could be ploughed by the forces of profit-pursuing private enterprise.’’

Eric Hobsbawn, Age of Revolution 1789 – 1848

Prior to 1789 ninety to ninety-seven percent of the Britain was rural where the relationship between those who cultivated the land produced its wealth for the benefit of those who owned the land. Industrialization changed this relationship and with the construction of factories a new workforce was created. It was the first time in human history that productive power could be constant and rapid allowing for the limitless multiplication of goods, services and consequently self-sustained growth. Three things happened to allow this shift in economic development. Firstly land was turned into a commodity, secondly this could be sold to self-interested profit seekers intent on developing it as a productive resource for the market and thirdly a large part of the rural population was transformed into wage-workers. Peasants were freed from their non-economic bonds and duties associated with the agrarian society and permitted to move freely into towns and factories where their labour was required. They were free to choose and open to the incentive of higher rewards and wages.

This changed society, provided the opportunity for talent, energy, shrewdness and greed to determine the futures of those who moved to the city rather than through birth right. It allowed individuals to progress, created accessible wealth and progress but it also generated greater social divide and consequentially un-unemployment and poverty. The old system provided greater security and certainty but the labour force if unemployed was isolated and un-protected.

Hobsbawn discusses the end of the Industrial Revolution as the time when the first railway network was completed and the Communist manifesto was published. With the freedom to pursue opportunity and wealth the general masses had moved into towns and cities in search of work and new social dynamics were established giving rise to new political and social ideologies. Cities changed, growing significantly and new institutions and ideas were established to protect and improve the urban environment for the benefit of the new city inhabitants. Space in cities became valuable and was developed removing many areas previously used for recreation, and the air became polluted.

Parks were recognised as sources of fresh air and a place for improving the health of those who worked in cities also accessible space for recreation. They were seen as a means of diffusing social tension and offered an alternative to the public house. Between 1833 and 1845 the Park Movement became recognisable but it wasn’t until 1875 that local authorities acquired full powers enabling them to create and maintain parks.

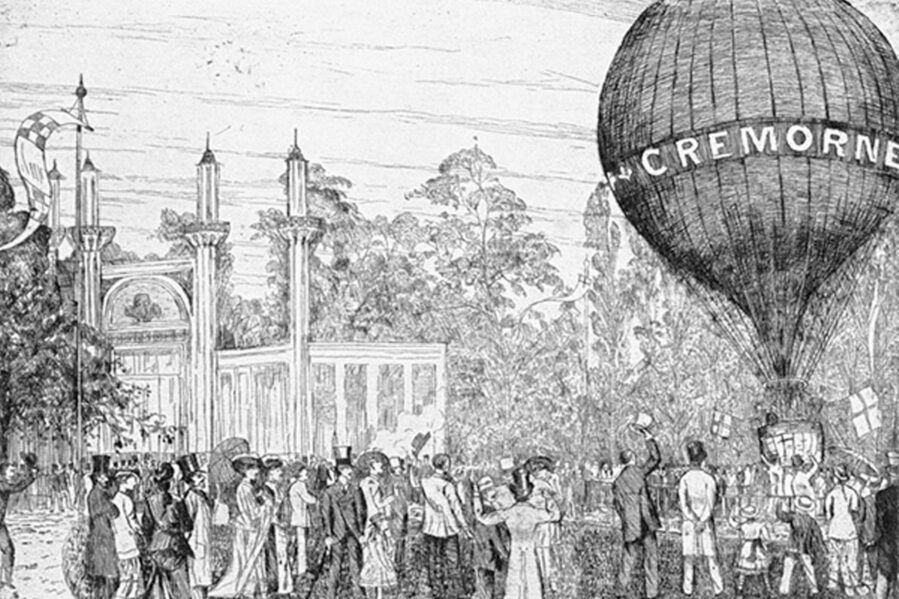

As local authorities sought to address major urban problems they developed a civic consciousness which was evident in the creation of parks but also the structures within. Lodges, pagodas, boathouses, refreshment rooms, and band-stands were erected in a range of architectural styles, exploiting new technologies and to extend the use of the parks for appropriate forms of entertainment. The public were keen to reward those with a capacity to entertain and the stage rose in social status illustrating the public’s need for escape and relief from the new industrialised and growing city. Parks offered greater social contact between the masses as their visitors tended to come from a broader cross-section of society. Parks and recreation were viable commercial ventures capitalising on the public’s need for entertainment. Pleasure gardens came alive at night with the largest providing complete centres for entertainment with music, drinking, balloon ascents and fireworks. Cremorne Gardens in Fulham opened in 1843 and included a, ‘monster pagoda’ surrounded by a circular platform which could accommodate 4,000 dancers, theatres, circus and American bowling saloon. Such environments delivered contrast and relief from the ordinary day to day working lives of their visitors.

‘This liberation from and reconciliation with the everyday is what made their visitors into playful crowds….. These playful crowds reflect their time and place’

‘The Playful Crowd’ -Gary S Cross & John K Walton

China’s Urbanisation

In 1978 Deng Xiaoping returned to the leadership after the Cultural Revolution and influenced market reform in China. At this time only twenty percent of China’s population lived in cities and the country was still largely rural with an outdated manufacturing sector and poor infrastructure.

Prior to market reform the movement of Chinese citizens’ was restricted and spilt between the urban and rural sectors. This division was enforced through the ‘hukou system’. Chinese cities differed from historic European cities. European cities developed from successful market towns. In China cities were primarily administrative centres which lacked political autonomy and were dependent on the countryside for resources. Commercial enterprise didn’t feature in urban life. Different policies affected the divided society with urban dwellers benefitting from state welfare, governed through work units and the rural population organised around People’s Communes.

Socialist urban policies were reversed in the 1980’s and the countryside went through rapid industrialisation. In the 1990’s inward capital investment shifted from rural industrialisation to focus on city centres. The People’s communes and work units were replaced by reformed state-owned enterprises and power shifted from central ministries to territorial authorities. The hukou system was reformed to allow people to move around to stimulate the economy. City governments became instrumental in promoting economic growth and social change. Special economic areas and development zones were designated with some cities declared, ‘Open Cities’ to attract foreign investment. Early success with pro-active policies to drive economic growth and attract investment secured urban policy revision to prioritise urban areas.

Land wasn’t previously a commodity and couldn’t be sold but the privatisation of land use rights made cheap land available to foreign investment. This strategy was enhanced in 1998 by allowing, ‘the right to use land to be transferred’ and therefore recognised market transactions of land. Urban governance has adopted strategies of urban entrepreneurialism, where they create alliances with independent organisations and developers to engage in competition with other areas to promote urban growth. The competition for investment and faster growth among localities has become rampant partly incentivised by the linked political fortunes of ambitious government officials.

This shift from rural to city-centred urbanisation reflected China’s integration into the world’s economy in the 90s. Through aggressive urbanisation over the last thirty years over four hundred cities have been established with hundreds of millions of new city residents. In 2010 about fifty percent of China’s national population lived in the city and China has become the world’s second largest economy next to America.

Such significant growth has affected the population, changing the distribution of wealth and benefits, producing new patterns of inequality and establishing an increasing number of middle class with disposable incomes. Cheap labour and free land are no longer enough to win the battle for investment. City authorities are turning to urban development and architecture to lure potential investors and inhabitants. There is an unusual mix between a market economy with authoritarian centralised control David Harvey calls this; ‘neoliberalism with Chinese characteristics’

China is facing a number of issues related to city development. Xuefei Ren describes three key issues, the need to allow public participation in policy making so that the emphasis moves away from political career concerns and GDP growth; co-operation between cities to reduce competition, and that cities need to be planned and built for people and not for profit to make them better places to live. New institutions and organisations are being established to address issues resulting from mass urbanisation and wealth imbalances as notions of citizenship and rights evolve.

China has established an urban middle class who are young, educated, career orientated with enough disposable income to take advantage of cultural offerings. The middle class is a broad social group defined by cultural capital, consumer choice and political orientation. They are the new driving force in China.

Pleasure, Release and Innovation

The industrial revolution in Europe created a migrant population which could be described as a, ’playful crowd’ in its pursuit of liberation from the everyday and harshness of the city. China’s industrialisation and subsequent mass urbanisation has similarly created an urban middle class seeking peace and security in China’s heaving metropolis. This has resulted in archipelagos of walled neighbourhoods, divided by dilapidated public space. Public space has lost its role as the area where people from all walks of life meet and socialise.

‘’ If the life in the metropolis creates loneliness and alienation, Coney Island counterattacks with Barrels of Love. Two horizontal cylinders – mounted in line - revolve slowly in opposite directions. At either end a small staircase leads up to an entrance. One feeds men into the machine, the other women. It is impossible to remain standing. Men and women fall on top of each other. The unrelenting rotation of the machine fabricates synthetic intimacy between people who would never otherwise have met.’’

Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York

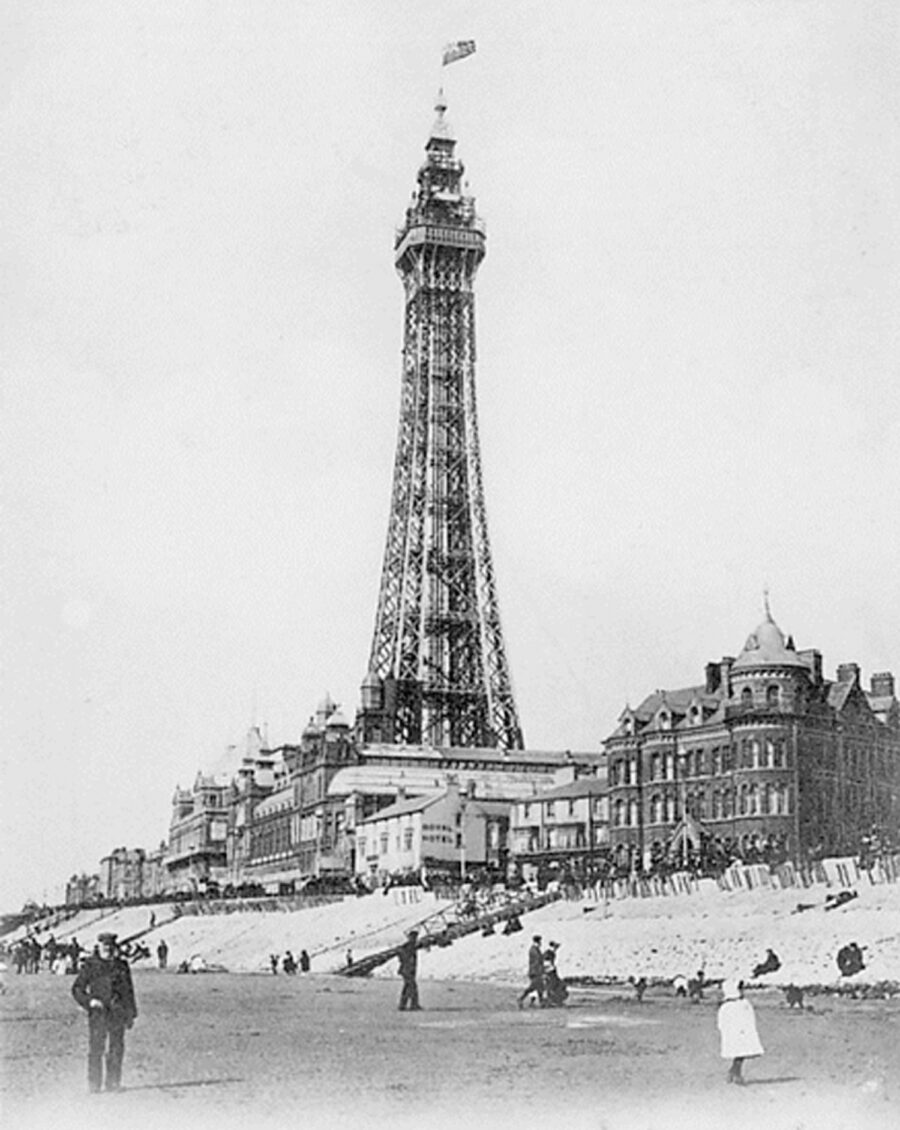

Resorts like Coney Island in New York and Blackpool in England provided a form of release from work and the city as well as opportunities for people of differing classes to mix. They creatively used technology in new ways to liberate and make fantasy more real to meet the expectations of a population whose appetite had been exaggerated by accelerated change. Both Blackpool and Coney Island are extreme examples of the Victorian pleasure parks, originated to overcome the worst excesses of urban expansion but Coney Island, New York and Blackpool owe their heritage to the great exhibitions. These phenomena were the cultural spawn of industry and empire, beginning with the Great Exhibition in London 1851, embellished by the French and pushed to its extreme by the Americans.

The intention of the original great exhibitions of Paris and London was to suspend the harshness of urban reality by promising material progress for all. Visitors were encouraged to dream of an imminently better life through the promise of progress and the intoxicating power of fantasy. As such the Eiffel Tower, Paris 1889, was not only a symbol of technological achievement but also a fun structure to climb up. Sir Joseph Paxton’s Crystal palace, a feat of engineering was 564m long, with an interior height of 39m. Made possible with the recent invention of the cast plate glass method in 1848, which allowed for large sheets of cheap but strong glass, it was, at the time, the largest amount of glass ever seen in a building and astonished visitors with its clear walls and ceilings that did not require lights, a "Crystal Palace" built to house of the best examples of manufacture and industry from around the world.

These exhibitions, supported by national associations operating in conjunction with government, gave hope to the people by demonstrating promising futures, progress and change. They were also focussed on the promotion of industry and exposed the country to international markets. The exhibitions and subsequent expositions were examples of modernity radically changing the old and transforming entertainment through technologically enhanced exaggeration. They gained legitimacy as a medium for national expression.

Inspired by London’s example, New York hosted its own world fair and built a version of Crystal Palace. It was a Pandora’s Box of inventions, including the elevator, which was presented to the world as a theatrical spectacle but was an invention that would go on to change the shape of the world.

‘’At the junction of the 19thand 20thcenturies, Coney Island is the incubator for Manhattan… The strategies and mechanisms that later shape Manhattan are tested in the laboratory of Coney Island…’’

Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York.

Between 1823 and 1860 Manhattan changes from a city to a metropolis and the need for escape becomes more urgent. The need for pleasure dominates and the arrival of the railway in 1865 connects the ocean front to the metropolitan masses. Dreamland a pleasure park is host to the beacon tower which rises 375ft above the park and becomes the most conspicuous structure. Illuminated with over 300 electric lights, the tower contains two elevators and from the top there is a bird’s eye view of the Coney Island. William H Reynolds president of Dreamland, twenty-five years later becomes the developer of the Chrysler Building. Manhattan became the theatre of architectural invention. Through experimentation, confidence and exuberance a distinct national identity is created. Manhattan demonstrates the possibility of the metropolis which develops its own specialised architecture.

Conclusion

Duanfang Lu in his book exploring architecture and identity discusses architecture development. He says that grandiose modernist buildings serve as a visible representation of a developing nation’s capacity to equal the developed nation on its own terms. Stylistic differentiation serves as an important strategy in the art of identity making. China has allowed the use of land to become a commodity and has adopted strategies of urban entrepreneurialism to engage in competition with other areas. Architecture and development have become physical manifestations of this competition and China doesn’t appear to be interested in being equal to the rest of the world but to surpass it. Similar to London, Paris and New York during their periods of major growth China’s cities want to exemplify the possibility of realising an imminently better life through the promise of progress and the intoxicating power of fantasy. The Chinese are used to ‘cobbling together’ conflicting ideas and making them work for a particular purpose. The rate of change is so dramatic that they have skipped the incubator stages provided through pleasure palaces and grand exhibitions and are implementing their utopian strategies in real time. The pressure to generate growth and secure foreign investment often excludes public participation. Cities need to be planned and built for people and not for profit to make them better places to live in. We in the west are witnessing huge expansion growth and experimentation by China and we need to be mindful not to presume that China is merely following our European trajectory from industrialisation and urbanism.

Our own histories demonstrate that fuelled by growth and economic confidence indulgence in experimentation has the potential to transform the way we live together and exist in our cities. We need to encourage this experimentation share our knowledge and engage in a dialogue which recognises cultural distinctiveness, geography, and is open to possibility. Not to be open to experimentation and exploration will result in a homogenous world of globalised similarity.

Bibliography

- Urban China; Xuefei Ren

- How the City Moved To Mr Sun; Daan Roggeveen

- Third World Modernism; Duanfang Lu

- Delirious New York; Rem Koolhaas

- Fair World, A History of World Fairs and Exhibitions London to Shanghai 1851-2010; Paul Greenhalgh

- The Playful Crowd, Pleasure Gardens in the 20thCentury; Gary S Cross & John K Walton

- People’s Parks, The Design and Development of Victorian Parks in Britain; Hazel Conway

- The Age of Revolution 1789-1848; Eric Hobsbawn